The Various Families of Instruments Are Grouped Together According to

Variety of recorders from Martin Agricola's 1529 Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Instrumental Music in German)

In the report of musical instruments, organology, there are many different methods of classifying musical instruments. Most methods are specific to a item cultural group and were developed to serve the requirements of that culture and its musical needs. Such classification schemes ofttimes break down when applied outside of their original context. For example, a classification based on musical instrument use may fail when applied to civilisation which has a different use, or fifty-fifty multiple uses, for the same instrument.

Throughout history, various methods of musical instrument classification take been used by musicians & scholars. The most commonly used system divides instruments into string instruments (ofttimes divided into plucked and bowed), wind instruments (frequently divided into woodwind and brass), and percussion instruments with modern classifications calculation electronic instruments as a singled-out class of instrument; however, other schemes have as well been devised.

Classification criteria [edit]

The criteria for classifying musical instruments vary depending on the signal of view, fourth dimension, and place. The many various approaches examine aspects such equally the physical backdrop of the instrument (shape, construction, material composition, physical land, etc.), the manner in which the instrument is played (plucked, bowed, etc.), the means by which the instrument produces audio, the quality or timbre of the sound produced by the instrument, the tonal and dynamic range of the instrument, the musical office of the musical instrument (rhythmic, melodic, etc.), and the musical instrument's place in an orchestra or other ensemble.

Classification systems by their geographical and historical origins [edit]

European and Western [edit]

2d-century Greek grammarian, sophist, and rhetoritician Julius Pollux, in the chapter called De Musica of his x-volume Onomastikon, presented the ii-form system, percussion (including strings) and winds, which persisted in medieval and postmedieval Europe. It was used by St. Augustine (4th and 5th centuries), in his De Ordine, applying the terms rhythmic (percussion and strings), organic (winds), and adding harmonic (the human voice); Isidore of Seville (sixth to 7th centuries); Hugh of Saint Victor (twelfth century), also adding the voice; Magister Lambertus (13th century), calculation the human vocalisation as well; and Michael Praetorius (17th century).[1] : 119–21, 147

The modernistic system divides instruments into wind, strings and percussion. It is of Greek origin (in the Hellenistic menses, prominent proponents being Nicomachus and Porphyry). The scheme was later expanded by Martin Agricola, who distinguished plucked string instruments, such as guitars, from bowed string instruments, such equally violins. Classical musicians today do not always maintain this division (although plucked strings are grouped separately from bowed strings in sheet music), but distinguish between wind instruments with a reed (woodwinds) and those where the air is fix in move directly by the lips (brass instruments).

Many instruments practice non fit very neatly into this scheme. The ophidian, for example, ought to be classified as a contumely instrument, as a column of air is ready in motion by the lips. Nevertheless, information technology looks more like a woodwind musical instrument, and is closer to one in many ways, having finger-holes to control pitch, rather than valves.

Keyboard instruments exercise non fit hands into this scheme. For example, the piano has strings, but they are struck by hammers, so it is not clear whether it should be classified every bit a string instrument or a percussion musical instrument. For this reason, keyboard instruments are often regarded as inhabiting a category of their own, including all instruments played by a keyboard, whether they have struck strings (similar the piano), plucked strings (like the harpsichord) or no strings at all (similar the celesta).

It might be said that with these extra categories, the classical system of instrument classification focuses less on the fundamental fashion in which instruments produce sound, and more on the technique required to play them.

Various names have been assigned to these 3 traditional Western groupings:[1] : 136–138, 157, notes for Chapter 10

- Boethius (5th and 6th centuries) labelled them intensione ut nervis, spiritu ut tibiis ("breath in the tube"), and percussione;

- Cassiodorus, a younger gimmicky of Boethius, used the names tensibilia, percussionalia, and inflatilia;

- Roger Bacon (13th century) dubbed them tensilia, inflativa, and percussionalia;

- Ugolino da Orvieto (14th and 15th centuries) called them intensione ut nervis, spiritu ut tibiis, and percussione;

- Sebastien de Brossard (1703) referred to them equally enchorda or entata (but merely for instruments with several strings), pneumatica or empneousta, and krusta (from the Greek for hit or strike) or pulsatilia (for percussives);

- Filippo Bonanni (1722) used vernacular names: sonori per il fiato, sonori per la tensione, and sonori per la percussione;

- Joseph Majer (1732) called them pneumatica, pulsatilia (percussives including plucked instruments), and fidicina (from fidula, fiddle) (for bowed instruments);

- Johann Eisel (1738) dubbed them pneumatica, pulsatilia, and fidicina;

- Johannes de Muris (1784) used the terms chordalia, foraminalia (from foramina, "bore" in reference to the bored tubes), and vasalia (for "vessels");

- Regino of Prum (1784) called them tensibile, inflatile, and percussionabile.

Mahillon and Hornbostel–Sachs systems [edit]

Victor-Charles Mahillon, curator of the musical musical instrument drove of the conservatoire in Brussels, for the 1888 catalogue of the collection divided instruments into four groups and assigned Greek-derived labels to the 4 classifications: chordophones (stringed instruments), membranophones (skin-head percussion instruments), aerophones (wind instruments), and autophones (non-skin percussion instruments). This scheme was afterwards taken upward past Erich von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs who published an all-encompassing new scheme for classification in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie in 1914. Their scheme is widely used today, and is most often known every bit the Hornbostel–Sachs arrangement (or the Sachs–Hornbostel system).

The original Sachs–Hornbostel system classified instruments into iv primary groups:

- idiophones, such every bit the xylophone, which produce audio by vibrating themselves;

- membranophones, such as drums or kazoos, which produce sound by a vibrating membrane;

- chordophones, such as the piano or cello, which produce sound past vibrating strings;

- aerophones, such as the piping organ or oboe, which produce sound past vibrating columns of air.

Later Sachs added a fifth category, electrophones, such as theremins, which produce sound by electronic means.[ii] Modernistic synthesizers and electronic instruments fall in this category. Within each category are many subgroups. The arrangement has been criticized and revised over the years, but remains widely used by ethnomusicologists and organologists. One notable example of this criticism is that care should be taken with electrophones, as some electronic instruments like the electric guitar (chordophone) and some electronic keyboards (sometimes idiophones or chordophones) tin can produce music without electricity or the use of an amplifier.

In the Hornbostel–Sachs classification of musical instruments, lamellophones are considered plucked idiophones, a category that includes various forms of jaw harp and the European mechanical music box, besides as the huge diversity of African and Afro-Latin thumb pianos such as the mbira and marimbula.

André Schaeffner [edit]

In 1932, comparative musicologist (ethnomusicologist) André Schaeffner adult a new classification scheme that was "exhaustive, potentially covering all real and conceivable instruments".[1] : 176

Schaeffner'southward organization has only two summit-level categories which he denoted by Roman numerals:

- I: instruments that make sound from vibrating solids:

- I.A: no tension (free solid, for instance, xylophones, cymbals, or claves);

- I.B: linguaphones (lamellophones) (solid fixed at only ane stop, such as a kalimba or pollex piano);

- I.C: chordophones (solid fixed at both ends, i.e. strings such as piano or harp); plus drums

- Ii: instruments that make sound from vibrating air (such as clarinets, trumpets, or bull-roarers.)

The system agrees with Mahillon and Hornbostel–Sachs for chordophones, but groups percussion instruments differently.

The MSA (Multi-Dimensional Scalogram Analysis) of René Lysloff and Jim Matson,[3] using 37 variables, including characteristics of the sounding torso, resonator, substructure, sympathetic vibrator, performance context, social context, and instrument tuning and construction, corroborated Schaeffner, producing two categories, aerophones and the chordophone-membranophone-idiophone combination.

André Schaeffner has been president of the French association of musicologists Société française de musicologie (1958-1967).[4]

Kurt Reinhard [edit]

In 1960, German language musicologist Kurt Reinhard presented a stylistic taxonomy, as opposed to a morphological one, with two divisions adamant by either single or multiple voices playing.[one] Each of these two divisions was subdivided according to pitch changeability (not changeable, freely changeable, and child-bearing by stock-still intervals), and besides by tonal continuity (discontinuous (every bit the marimba and drums) and continuous (the friction instruments (including bowed) and the winds), making 12 categories. He besides proposed classification according to whether they had dynamic tonal variability, a feature that separates whole eras (e.g., the baroque from the classical) as in the transition from the terraced dynamics of the harpsichord to the crescendo of the piano, grading past caste of absolute loudness, timbral spectra, tunability, and degree of resonance.

Steve Isle of man [edit]

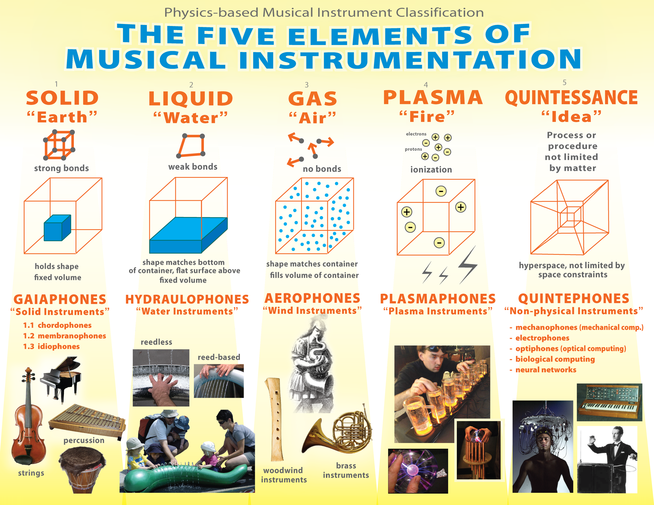

In 2007, Steve Isle of mann presented a five-class, physics-based organology elaborating on the classification proposed by Schaeffner.[five] This arrangement is composed of gaiaphones (chordophones, membranophones, and idiophones), hydraulophones, aerophones, plasmaphones, and quintephones (electrically and optically produced music), the names referring to the five essences, globe, water, wind, fire and the quintessence, thus adding 3 new categories to the Schaeffner taxonomy.

Simple organology, besides known every bit physical organology, is a classification scheme based on the elements (i.e. states of matter) in which audio product takes place.[6] [vii] "Uncomplicated" refers both to "element" (state of matter) and to something that is fundamental or innate (concrete).[8] [9] The elementary organology map tin can be traced to Kartomi, Schaeffner, Yamaguchi, and others,[viii] also as to the Greek and Roman concepts of elementary classification of all objects, not only musical instruments.[eight]

Elementary organology categorizes musical instruments by their classical chemical element:

| Element | Land | Category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | Earth | solids | gaiaphones | the first category proposed by Andre Schaeffner[10] |

| two | Water | liquids | hydraulophones | |

| 3 | Air | gases | aerophones | the 2d category proposed past Andre Schaeffner[x] |

| 4 | Burn | plasmas | plasmaphones | |

| five | Quintessence/Idea | informatics | quintephones |

Instrument classification in physics-based organology.

Other Western classifications [edit]

Classification by tonal range [edit]

Instruments can be classified by their musical range in comparison with other instruments in the same family. These terms are named afterward singing voice classifications:

- Higher-than-sopranino instruments: the garklein recorder in C (also known every bit the sopranissimo recorder, or piccolo recorder), soprillo saxophone, piccolo

- Sopranino instruments: sopranino recorder, sopranino saxophone, treble flute

- Soprano instruments: concert flute, clarinet, soprano recorder, violin, trumpet, oboe, soprano saxophone

- Alto instruments: alto flute, alto recorder, viola, French horn, natural horn, alto horn, alto clarinet, alto saxophone, English horn

- Tenor instruments: trombone, euphonium, tenor violin, tenor flute, tenor saxophone, tenoroon, tenor recorder, bass flute

- Baritone instruments: cello, baritone horn, bass clarinet, bassoon, baritone saxophone

- Bass instruments: bass recorder, bass oboe, bass tuba, bass saxophone, bass trombone

- Lower-than-bass instruments: contrabass tuba, double bass, contrabassoon, contrabass clarinet, contrabass saxophone, subcontrabass saxophone, tubax, octobass

Some instruments autumn into more than 1 category: for example, the cello may be considered either tenor or bass, depending on how its music fits into the ensemble, and the trombone may exist alto, tenor, or bass and the French horn, bass, baritone, tenor, or alto, depending on which range it is played. In a typical concert ring setting, the offset alto saxophone covers soprano parts, while the second alto saxophone covers alto parts.

Many instruments include their range equally role of their name: soprano saxophone, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, baritone horn, alto flute, bass flute, bass guitar, etc. Additional adjectives draw instruments above the soprano range or below the bass, for instance: sopranino recorder, sopranino saxophone, contrabass recorder, contrabass clarinet.

When used in the proper noun of an instrument, these terms are relative, describing the instrument's range in comparison to other instruments of its family and not in comparison to the human voice range or instruments of other families. For example, a bass flute's range is from C3 to F ♯ six, while a bass clarinet plays about one octave lower.

Classification by role [edit]

Instruments can be categorized according to typical use, such as signal instruments, a category that may include instruments in unlike Hornbostel–Sachs categories such as trumpets, drums, and gongs. An example based on this criterion is Bonanni (e.yard., festive, military, and religious).[1] He separately classified them co-ordinate to geography and era.

Instruments tin be classified co-ordinate to the role they play in the ensemble. For example, the horn section in pop music typically includes both brass instruments and woodwind instruments. The symphony orchestra typically has the strings in the front, the woodwinds in the center, and the basses, brass, and percussion in the back.

Classification by geographical or ethnic origin [edit]

Jean-Benjamin de la Borde (1780) classified instruments according to ethnicity, his categories being Black, Abyssinian, Chinese, Standard arabic, Turkish, and Greek.[1]

Westward and Southward Asian [edit]

Indian [edit]

An ancient system of Indian origin, dating from the 4th or third century BC, in the Natya Shastra, a theoretical treatise on music and dramaturgy, by Bharata Muni, divides instruments into four main nomenclature groups: instruments where the sound is produced by vibrating strings (tata vadya, "stretched instruments"); instruments where the sound is produced by vibrating columns of air (susira vadya, "hollow instruments"); percussion instruments made of woods or metallic (Ghana vadya, "solid instruments"); and percussion instruments with skin heads, or drums (avanaddha vadya, "covered instruments").

Persian [edit]

Al-Farabi, Farsi scholar of the tenth century, distinguished tonal duration. In one of his four schemes, in his 2-volume Kitab al-Musiki al-Kabir (Cracking Book of Music) he identified 5 classes, in social club of ranking, as follows: the human voice, the bowed strings (the rebab) and winds, plucked strings, percussion, and trip the light fantastic toe, the first 3 pointed out every bit having continuous tone.

Ibn Sina, Persian scholar of the 11th century, presented a scheme in his Kitab al-Najat (Volume of the Commitment), made the same distinction. He used two classes. In his Kitab al-Shifa (Book of Soul Healing), he proposed another taxonomy, of v classes: fretted instruments; unfretted (open) stringed, lyres and harps; bowed stringed; wind (reeds and some other woodwinds, such equally the flute and bagpipe), other wind instruments such as the organ; and the stick-struck santur (a lath zither). The distinction between fretted and open was in classic Persian fashion.

Turkish [edit]

Ottoman encyclopedist Hadji Khalifa (17th century) recognized three classes in his Kashf al-Zunun an Asami al-Kutub wa al-Funun ("Description and Theorize About the Names of Books and Sciences"), a treatise on the origin and construction of musical instruments. but this was exceptional for Almost Eastern writers as they mostly ignored the percussion group as did early Hellenistic Greeks, the Almost Eastern culture traditionally and that period of Greek history having low regard for that grouping.[1]

East and South-East Asian [edit]

Chinese [edit]

The oldest known scheme of classifying instruments is Chinese and may engagement every bit far back every bit the 2d millennium BC.[xi] It grouped instruments according to the materials they are made of. Instruments made of stone were in ane group, those of wood in another, those of silk are in a 3rd, and those of bamboo in a fourth, equally recorded in the Yo Chi (record of ritual music and dance), compiled from sources of the Chou period (9th–5th centuries BC) and corresponding to the four seasons and four winds.[i] [12]

The eight-fold system of eight sounds or timbres (八音, bā yīn), from the same source, occurred gradually, and in the legendary Emperor Shun's time (tertiary millennium BC) it is believed to take been presented in the following society: metal (金, jīn), stone (石, shí), silk (絲, sī), bamboo (竹, zhú), gourd (匏, páo), clay (土, tǔ), leather (革, gé), and woods (木, mù) classes, and it correlated to the viii seasons and eight winds of Chinese civilization, fall and west, autumn-winter and NW, summer and south, spring and east, wintertime-spring and NE, summer-autumn and SW, wintertime and northward, and spring-summertime and SE, respectively.[one]

Still, the Chou-Li (Rites of Chou), an anonymous treatise compiled from before sources in about the 2nd century BC, had the following guild: metal, stone, clay, leather, silk, forest, gourd, and bamboo. The same order was presented in the Tso Chuan (Commentary of Tso), attributed to Tso Chiu-Ming, probably compiled in the 4th century BC.[1]

Much afterwards, Ming dynasty (14th–17th century) scholar Chu Tsai Yu recognized iii groups: those instruments using muscle power or used for musical accessory, those that are blown, and those that are rhythmic, a scheme which was probably the first scholarly try, while the before ones were traditional, folk taxonomies.[13]

More ordinarily, instruments are classified according to how the sound is initially produced (regardless of postal service-processing, i.due east., an electric guitar is still a cord-instrument regardless of what analog or digital/computational postal service-processing effects pedals may be used with information technology).

Indonesian [edit]

Classifications done for the Indonesian ensemble, the gamelan, were done by Jaap Kunst (1949), Martopangrawit, Poerbapangrawit, and Sumarsam (all in 1984).[one] Kunst described five categories: nuclear theme (cantus firmus in Latin and balungan ("skeletal framework") in Indonesian); colotomic ( a word invented by Kunst) (interpunctuating), the gongs; countermelodic; paraphrasing (panerusan), subdivided as close to the nuclear theme and ornamental filling; agogic (tempo-regulating), drums.

R. Ng. Martopangrawit has two categories, irama (the rhythm instruments) and lagu (the melodic instruments), the former corresponds to Kunst's classes 2 and five, and the latter to Kunst'due south 1, 3, and 4.

Kodrat Poerbapangrawit, like to Kunst, derives six categories: balungan, the saron, demung, and slenthem; rerenggan (ornamental), the gendèr, gambang, and bonang); wiletan (variable formulaic melodic), rebab and male chorus (gerong); singgetan (interpunctuating); kembang (floral), flute and female phonation; jejeging wirama (tempo regulating), drums.

Sumarsam's scheme comprises

- an inner melodic grouping (lagu)(with a wide range), divided as

- elaborating (rebab, gerong, gendèr (a metallophone), gambang (a xylophone), pesindhen (female voice), celempung (plucked strings), suling (flute));

- mediating ( betwixt the 1st and 3rd subdivisions (bonang (gong-chimes), saron panerus(a loud metallophone); and

- abstracting (balungan, "melodic brainchild")( with a 1-octave range), loud and soft metallophones (saron barung, demung, and slenthem);

- an outer circle, the structural grouping (gongs), which underlines the structure of the work;

- and occupying the space outside the outer circle, the kendang, a tempo-regulating group (drums).

The gamelan is too divided into front, middle, and back, much similar the symphony orchestra.

An orally transmitted Javanese taxonomy has viii groupings:[ane]

- ricikan dijagur ("instruments browbeaten with a padded hammer," eastward.g., suspended gongs);

- ricikan dithuthuk ("instruments knocked with a hard or semihard hammer," e.one thousand., saron (similar to the glockenspiel) and gong-chimes);

- ricikan dikebuk ("hand-beaten instruments", e.yard., kendhang (drum));

- ricikan dipethik ("plucked instruments");

- ricikan disendal ("pulled instruments," e.grand., genggong (jaw harp with string mechanism));

- ricikan dikosok ("bowed instruments");

- ricikan disebul ("blown instruments");

- ricikan dikocok ("shaken instruments").

A Javanese classification transmitted in literary form is every bit follows:[1]

- ricikan prunggu/wesi ("instruments made of bronze or iron");

- ricikan kulit ("leather instruments", drums);

- ricikan kayu ("wooden instruments");

- ricikan kawat/tali ("string instruments");

- ricikan bambu pring ("bamboo instruments", eastward.g., flutes).

This is much similar the pa yin. Information technology is suspected of existence old merely its historic period is unknown.

Minangkabau musicians (of West Sumatra) utilise the following taxonomy for bunyi-bunyian ("objects that sound"): dipukua ("beaten"), dipupuik ("blown), dipatiek ("plucked"), ditariek ("pulled"), digesek ("bowed"), dipusiang ("swung"). The final one is for the bull-roarer. They also distinguish instruments on the basis of origin because of sociohistorical contacts, and recognize three categories: Mindangkabau (Minangkabau asli), Standard arabic (asal Arab), and Western (asal Barat), each of these divided up co-ordinate to the five categories. Classifying musical instruments on the basis sociohistorical factors too equally style of audio production is common in Indonesia.[i]

The Batak of North Sumatra recognize the following classes: browbeaten (alat pukul or alat palu), diddled (alat tiup), bowed (alat gesek), and plucked (alat petik) instruments, merely their primary classification is of ensembles.[1]

Philippine [edit]

The T'boli of Mindanao use three categories, grouping the strings (t'duk) with the winds (nawa) together based on a gentleness-force dichotomy (lemnoy-megel, respectively), regarding the percussion group (tembol) as stiff and the winds-strings group as gentle. The division pervades T'boli thought about cosmology, social characters of men and women, and artistic styles.[one]

African [edit]

West African [edit]

In Westward Africa, tribes such as the Dan, Gio, Kpelle, Hausa, Akan, and Dogon, use a homo-centered system. It derives from four myth-based parameters: the musical musical instrument's nonhuman owner (spirit, mask, sorcerer, or animal), the mode of transmission to the human realm (by gift, exchange, contract, or removal), the making of the instrument by a human (according to instructions from a nonhuman, for example), and the kickoff human owner. Most instruments are said to accept a nonhuman origin, simply some are believed invented by humans, e.g., the xylophone and the lamellophone.[one]

The Kpelle of West Africa distinguish the struck (yàle), including both browbeaten and plucked, and the diddled (fêe).[one] [14] The yàle grouping is subdivided into five categories: instruments possessing lamellas (the sanzas); those possessing strings; those possessing a membrane (diverse drums); hollow wooden, iron, or bottle containers; and various rattles and bells. The Hausa, besides of West Africa, classify drummers into those who beat drums and those who beat (pluck) strings (the other four actor classes are blowers, singers, acclaimers, and talkers),[15]

Meet also [edit]

- Classification of percussion instruments

- Organology

- List of musical instruments

- Indicate musical instrument

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j k l m n o p q r Kartomi, Margaret J. (1990-11-01). On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. University of Chicago Printing.

- ^ The History of Musical Instruments, C. Sachs, Norton, New York, 1940

- ^ A New Arroyo to the Classification of Audio-Producing Instruments, Ethnomusicology, Spring/Summer, 1985, also at mywebspace.wisc.edu

- ^ "La SFM en quelques dates: présidée par les musicologue suivants". sfmusicologie.fr/ . Retrieved 2021-07-15 .

- ^ Mann, Steve (2007). Natural Interfaces for Musical Expression, Proceedings of the Briefing on Interfaces for Musical Expression. New Interfaces for Musical Expression. pp. 118–23.

- ^ Calculator Music Journal Autumn 2008, Vol. 32, No. 3, Pages 25–41 Posted Online August 15, 2008. doi:10.1162/comj.2008.32.3.25

- ^ The Grove Lexicon of Musical Instruments (two ed.), Oxford University Press, Print ISBN 9780199743391, 2016, Edited by Laurence Libin.

- ^ a b c Physiphones, NIME 2007, New York, pp118-123

- ^ Computer Music Periodical Fall 2008, Vol. 32, No. 3, Pages 25–41

- ^ a b Kartomi, page 176, "On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments", by Margaret J. Kartomi, Academy of Chicago Press, Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology (CSE), 1990

- ^ Hast, Dorothea Due east. (1999). Exploring the Earth of Music: An Introduction to Music from a World Music Perspective. Debuque, IA: Kendall Chase. p. 144. ISBN0787271543.

- ^ Rowell, Lewis Eugene (1992). Three Ancient Conceptions of Musical Sound. Music and Musical Thought in Early Republic of india. Academy of Chicago Press. p. 54.

- ^ Margaret Kartomi, 2011, Upward and Down Classifications of Musical Instruments-musicology.ff,cuni.cz)

- ^ Ruth Stone, "Allow the Inside Be Sweet: the interpretation of music among the Kpelle of Republic of liberia", 1982, Indiana U. Printing

- ^ Ames and King. Glossary of Hausa Music and its Social Contexts, 1971, Northwestern U. Printing.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical_instrument_classification

0 Response to "The Various Families of Instruments Are Grouped Together According to"

Postar um comentário